2019 marks a year of change, but not transcendence in Thailand. The National Council for Peace (NCPO) is now defunct, after more than five years and one month since the military coup. The general election was followed by the return of the same old Prime Minister, the same face and the same name, plus the proliferation of the NCPO’s political power on various fronts and the perpetuation of the Military’s political clout.

The past year’s human rights situation, particularly with regard to political rights and judicial rights, saw some improvements, including the transfer of some of the cases against civilians from military to civilian courts, the revocation of the ban on political gatherings of five persons and upward, and a decline in the number of individuals summoned for attitude adjustment in military barracks.

Yet a number of human rights violations persist, along with the same Prime Minister, particularly the prosecutions against the exercise of the right to freedom of expression, the lawsuits filed to silence and impose a burden upon political critics, and various other forms of harassment and intimidation, the kind of infringement which continues unabated and seems to have been normalized.

As the year is drawing to its close, Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR) presents here twelve cases which represent the most egregious human rights violations of the past year and how similar cases may happen in the following year.

Harassments and attacks of pro-democracy activists with no one brought to justice

As the country braced itself for elections earlier this year, there was a spike of human rights violations, including physical assaults, against three pro-democracy activists who had been quite vocal against the seizure of power by the NCPO, namely Ekkachai Hongkangwan, Anurak Jeantawanich, aka “Ford the Red Path” and Sirawith Seritiwat, aka “Ja New”. They all were physically attacked in public places. Since early 2019, they have been subject to at least seven attacks. The three activists insist none of the incidences had anything to do with personal conflicts with anyone.

It should be noted, however, that all the attacks happened either before or after their participation in political activities. The attacks were well coordinated; they were tracked and ambushed by individuals lurking and waiting to attack them. All culprits were wearing safety helmets to hide their identities and managed to escape leaving minimal traces in CCTV footage.

In addition, Ekkachai had his personal vehicle set on fire twice. Parit Chiwarak, aka ‘Penguin’, another prominent pro-democracy activist, received a phone call from someone who threatened to attack him. Although several such attacks happened throughout 2019, none of the perpetrators have been brought to justice.

The well-coordinated physical attacks could be an attempt to send a signal concerning the impending change of political power. It could also be a new tool to replace conventional intimidation, surveillance and legal actions against pro-democracy activists. Given that no progress has been made as in the attempt to bring the perpetrators to justice, they will likely gain confidence about the impunity they enjoy and increase the violence of future attacks. Allowing such incidences to take place while the perpetrators go unpunished only fuels the attackers’ determination at the expense of societal safety.

The NCPO has ended, but “home visitations” have not

(Picture from Titipol Phakdeewanich)

Even though the NCPO and Peace and Order Maintaining Command are now defunct, the form of human rights violation whereby public officials go unannounced to “meet” individuals at their homes, universities, schools, workplaces, or private living quarters, has not stopped since the 2014 coup.

This practice has occurred when the individuals have commented publicly about politics and have consequently been approached by officials, who ask them to stop making such comments without invoking any legal power. One example is the harassment of Mr. Yan Marshall, a French national living in Thailand who produced a video clip parodying the song “Return Happiness to Thailand”. This prompted the police to visit him at home and he was forced to remove the clip from the internet and to sign a paper acknowledging that the uploading of the clip was extremely improper and that he would not do it again.

In addition, individuals on a watchlist are often subject to close vigilance before or during an important event or day (such as the ASEAN Summit), regardless of whether those individuals show any intent to carry out any political activities. Throughout 2019, public officials would often check in with targeted individuals who may have participated in political gatherings in the past. They even visited them at their homes asking them to not take part in any activities. Similar visits happened just prior to the Royal Coronation in May and December.

Moreover, on the verge of any mass mobilization on issues concerning natural, land, or forest resources, including demonstrations on important issues in Bangkok, officials would approach the organizers and core members of the grassroots groups at their homes. One such case concerned members of the Assembly of the Poor (AOP), who took to the street in October to demand the government help resolve their concerns. Prior to the demonstration, military and police officials reportedly approached them at their homes in more than 34 areas.

Such breaches of the right to privacy and freedom of expression have been normalized and have taken place over the past several years with no end in sight.

Extrajudicial process used to detain individuals who comment on the monarchy

Although prosecutions under Section 112 have been on the decline, TLHR has found harassment against those who comment on the monarchy continues unabated, despite the fact that the comments are not offensive or defamatory, or may simply be shared or retweeted posts. Extrajudicial procedures carried out by public officials include search, detention, requesting of personal information, and coercion to commit to an agreement, none of which are carried out under judicial purview or legal sanction.

A glaring case took place in November 2019 whereby a Twitter user by the alias of @99CEREAL recounted how she was held in custody by officials who claimed to ‘invite’ her from her university to the police station without showing her any judicial warrant. This stemmed from her retweeting posts by people including Somsak Jeamteerasakul and an individual with the alias “Niranam”, and retweeting foreign news about issues in Thailand.

The Twitter user recalled how at the police station, about a dozen officials from an unidentified unit surrounded and interrogated her about her political opinions and personal background. The entire interrogation session was video-taped and photographed. A transcript of the inquiry was also made. They asked to take photos of her phone’s IP address, Twitter login name, her phone numbers and email addresses. They even asked to see all of her online chats. She was eventually forced to sign an MoU stating that she would no longer tweet anything about the monarchy.

TLHR has found a number of other online users who have been subject to such treatment, although the exact number is unknown since most of them are too scared to reveal any information. Such incidents occur whenever comments are made on various issues related to the monarchy. This has led to online trends including the hashtag #RoyalMotorcade on Twitter and the refusal to stand up for the Royal Anthem in movie theatres.

When independent agencies do not tolerate criticism, legal actions against the public become their tool

(Picture from 77 Khaoded)

The 24 March 2019 election gave rise to much controversy and allegations of its rampant lack of transparency and clarity. The electoral process has been designed with insidious purposes and been made rather complicated. It has even been said that “the constitution has been designed to serve us.” Meanwhile, the independent agency which held the election, the Election Commission of Thailand (ECT), has failed to impress the public with their performance in terms of the organization of the election itself and the following vote counting and calculation, which even stunned mathematicians. This has all led to the proliferation of the NCPO’s power, even if it has organizationally become defunct.

Doubts about the ECT’s integrity led to a campaign to impeach ECT members via Change.org. More than 849,000 people have signed the online petition. In another campaign, “One Million Signatures to Remove #ECT, Exposed!”, kiosks were set up for people to sign a petition which would be submitted to the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC) to conduct an investigation into the ECT’s performance. It managed to collect 7,234 signatures in total (for more detail, please see The rugged path to collect signatures to impeach ECT)

The ECT, whose performance has been widely criticized, instead of suspending its work, filed a case against seven members of the public accusing them of committing libel as result of their campaign to have the ECT members removed on Change.org. The ECT claims the campaign tarnished their image, subjecting them to hatred or scorn. Moreover, the ECT has filed a case against three other members of the public accusing them for committing the same offence as a result of their making public speeches during the campaign to collect signatures to impeach the ECT with a hashtag which translates as #Don’tYouCareAboutMe and their criticism of the ECT’s performance.

The legal actions against members of the public who have come out to demand the accountability of independent agencies have turned into an attempt to stifle criticisms made by people who pay the taxes which fund those same agencies. It reinforces the notion that the so-called justice process is being used as a tool to silence and restrict the public, undermining their ability to ask questions, to investigate or to demand responsibility from public agencies.

When opposition parties become a target of judicial harassment

(Picture from Prachatai)

Another prominent phenomenon this year concerned opposition parties, particularly parties which are blatantly opposed to the proliferation of the coup-makers’ power. Parties should face political opposition, but beyond fair political competition, opposition parties have had to face many legal actions targeting executive members (some of whom had been charged since the military junta was in power, before the general election) and even the parties themselves, for example, the Thai Raksa Chart Party which was eventually disbanded by the Constitutional Court and its executive members stripped of their political rights.

The Future Forward Party (FFP), a rising new party recently-formed, was accused of breaking the Computer Crimes Act as a result of its criticizing the NCPO’s party of using money to ‘suck in’ candidates from other political parties since 2018. More criminal cases and cases related to the election have been filed against the party’s members including Piyabutr Saengkanakkul, the party’s Secretary General, who was accused of contempt of court and for putting false data into a computer system as a result of a press conference in which he criticized the Constitutional Court’s verdict on the dissolution of the Thai Raksa Chart Party. The party’s leader, Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit was also slapped with a series of cases just ten days after the election. Many of such legal cases have stemmed from his past acts, i.e., for showing his solidarity with the 14 pro-democracy activists who were members of the “New Democracy Movement” at the Pathumwan police station on 24 June 2015.

The ECT continues to file cases against the Future Forward Party (FFP) with the Constitutional Court including one in which Thanathorn was disqualified as a Member of Parliament as a result of his alleged holding of shares in a media company. Recently, the ECT filed the case against the FFP with the Constitutional Court as a result of financial loans Thanathorn made to the party.

In a landmark case, several members of opposition parties have been charged as a result of their speaking at a panel discussion on “The Dynamisms of Solutions for Problems in the Deep South: a fresh start toward a new constitution”. Twelve academics and opposition politicians who spoke at the event now face a sedition case filed by the ISOC Region 4 Forward simply because one of the panelists, Chalita Bundhuwong, a faculty member from Kasetsart University, ended her speech by proposing that a chance should be made available to debate the possible amendment of all sections of the Constitution including, if need be, Section 1 (about Thailand being a unitary state).

All these seem to fit the notion of ‘lawfare’; how the law and the justice process have been used as tools to gain political leverage and victories as well as to defeat political opponents. Eventually, the misuse of law in such manners could undermine the rule of law in Thailand.

The year of abuse of the Computer Crimes Act to stifle online freedom of expression

2019 is probably the year the Computer Crimes Act has most frequently been used to suppress the exercise of freedom of expression. It has led to a climate of fear, whereby the public are too scared to criticize the performance of the government or to express their political opinions online. It has led to the retraction of debate on certain issues, making people concerned about the legal consequences of online political engagement, including being charged with an offence against the Computer Crimes Act.

One of the most glaring examples is the case against Kant Pongpraphan, a 25-year-old pro-democracy activist who was accused of violating Section 14(3) of the Computer Crimes Act (“putting into a computer system false computer data in a manner that is likely to damage the maintenance of national security”) during the trending of the hashtag #RoyalMotorcade.

During 2019 TLHR has been asked to assist in eight new legal cases related to the violation of the Computer Crimes Act including the case against a lecturer from Chiang Mai University and Red Shirt activist as a result of their social media posts to mock the military by jokingly suggesting the military were participating in the “Walk to Vote” gathering; the case of a military official convicted for making a post about politics; and the case of a social media post alleging that the police were complicit in physical attacks against Ja New.

It should be noted as well that whereas in the past the trend had been to file cases invoking both the Computer Crimes Act in tandem with Section 112 or 116 of the Penal Code, TLHR has found an increase of politically motivated cases filed solely invoking the breach of the Computer Crimes Act. The exclusive use of the CCA seems to be replacing the use of Sections 112 and 116 of the Penal Code in order to suppress the expression of political opinion online. The future direction of the use of the Computer Crimes Act to stifle freedom of expression thus warrants further vigilance.

What is a public assembly? How might an act be construed as a public assembly?: Restriction of freedom of assembly through the Public Assembly Act

(Picture form Wassana Nanuam)

Despite the general election, the Public Assembly Act 2015, enacted by the NCPO-appointed National Legislative Assembly (NLA), is still frequently used, particularly Chapter 2 on the notification of public assembly. If one fails to notify authorities in advance, it is likely that one will not be able to hold a public assembly. Even after the public assembly has been organized, one can still face a legal action.

In the past year, activists and members of the public have continued to face legal action as a result of holding a public assembly without notification. Examples include, Phayaw Akkahad, aka “ Mae Nong Ket”, who performed in a pantomime at Democracy Monument; Ekkachai and Chokchai who played the song “Rap against Dictatorship”; and Penguin-Ball for playing the song “The Traitors” (Nak Phaen Din) at the entrance of the Royal Thai Army Headquarters.

TLHR notes that certain public assemblies with no bearing on politics may be organized without necessary notification. This sheds light on the flaws of the Public Assembly Act, which uses overly broad definitions and makes possible discriminatory enforcement. These include for example the definition of “public assembly” (Section 4); the public assembly notification (Section 10); and the requirement that a public assembly must be held outside a radius of 150 meters from a royal residence (Section 7). The organizers of some public assemblies have been charged as a result, including the case of Ja New and members of the public for setting up tables in Chiang Rai to collect signatures for a petition to impeach the 250 Senators; and the case of Penguin-Ball, for hanging chili and salt on the fences of Government House, who was later was charged for failing to notify authorities of a public assembly. Meanwhile, a public assembly in front of the Bangkok Art & Culture Centre, involving the symbolic action of standing with open umbrellas to show solidarity with protesters in Hong Kong, faced no legal action.

Despite lifting the ban on political gatherings of five persons and upward per a Head of the NCPO Order, freedom of public assembly continues to face restriction as a result of the Public Assembly Act, which should instead be used to uphold the freedom of public assembly of members of the public and restrict the use of power by public officials.

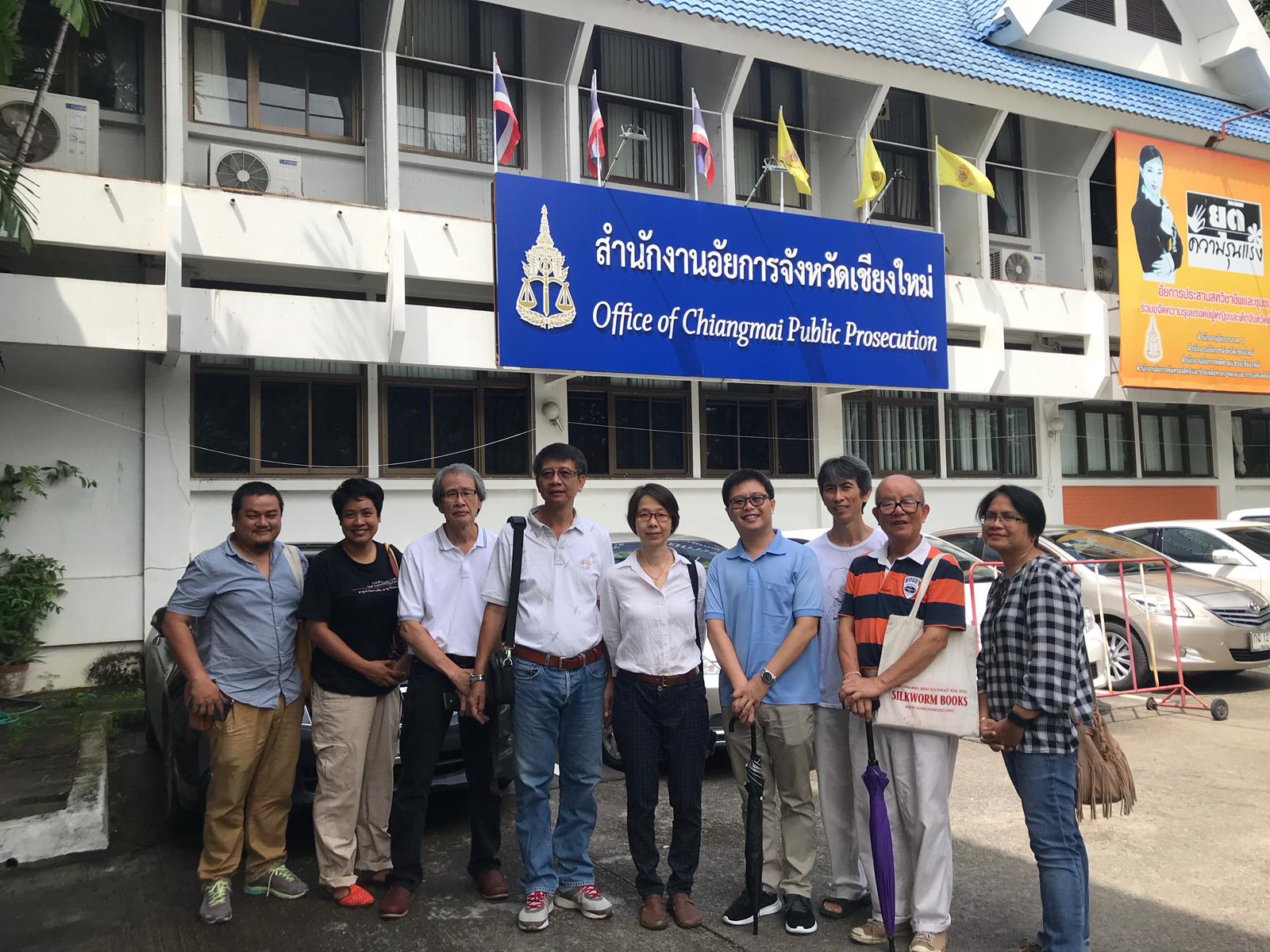

No more use of military courts, but politically motivated cases from the coup-era continue to languish in civilian courts

The trying of civilians in military courts was a major human rights violation under the rule of the NCPO. The Head of the NCPO, Gen. Prayuth Chan-ocha, invoked his power per Section 44 to issue Head of the NCPO Order no. 9/2562 to transfer all politically-motivated cases against civilians from the jurisdiction of military courts to civilian courts, without having any bearing on the trials already conducted in the military court.

The latter half of the year saw the gradual transfer of a number of politically-motivated cases related to Sections 112 and 116 of the Penal Code, breaches of an NCPO summons, or the bearing of firearms to civilian courts in various areas. Hearing scheduled were also announced. Many cases have been ongoing for nearly six years, but there is no end in sight due to the protracted witness examination procedure adopted by the military court. The transfer of the cases to civilian courts should help to accelerate the trials.

Still, questions can be raised about the rights in the justice process in many of these cases including the right to appeal to Courts of higher instances. During the time Marital Law was imposed following the 2014 coup, defendants tried in the military court were deprived of their right to appeal to a court of higher instances. The trials were held in a single tier court. Given that such cases have now been transfer to the Court of Justice, it is unclear whether parties may appeal to courts of higher instances.

Apart from many procedural flaws, a number of cases against civilians which were tried in military courts should not have been prosecuted. Many of them were related to the exercise of the right to freedom of expression and freedom of political opinions, and many stemmed from the suspects being held in military barracks during interrogation. Such testimonies have been used as incriminating evidence to apply for arrest warrants from the military court. The NCPO’s military officials became the plaintiffs and participated in the investigation process, and the cases were prosecuted by military prosecutors who appear to lack independence.

Decisions made based on the discretion of either military prosecutors or military court judges during the coup era have been passed on to civilian prosecutors and civilian courts. The continued prosecution of such politically motivated cases against members of the public is a remnant from the use of draconian power by the coup-makers (for more detail, please see Problems concerning the transfer of politically motivated cases from military court)

Contempt of Court: yet another effort to stifle critics of judicial process

(Picture from Matichon Weekly)

2019 also saw the use of “contempt of court”, a Civil Code offence, which has given rise to debate about law enforcement on one hand and the upholding of freedom to criticize on the other. Following the publishing of an article in Krungthep Turakij by renowned author and financial columnist, Sarinee Achavanuntakul, a case was filed against her by former Secretary of Election Cases of the Supreme Court, allegedly for her inappropriate word choice in her critique of the Supreme Court’s verdict regarding a court order to invalidate a Future Forward Party (FFP) member’s candidacy in the Sakon Nakhon election.

The Supreme Court eventually dropped the case following mediation between the parties, but the judicial proceedings before the case was dropped spanned nearly three months and incurred quite a burden on the accused. It also raises questions about the extent to which a critique of the judiciary can be made.

Another prominent case involved Associate Professor Kovit Wongsurawat, a lecturer at Kasetsart University and Yutthalert “Tom” Limpaparb, a well-known filmmaker. The two were “invited’ by the Constitutional Court for a meeting following their Twitter posts criticizing the Court. It is unclear what legal power the Court invoked to invite them to the meeting.

Meanwhile, there are ongoing contempt of court cases that have lingered from the NCPO era, including the case against seven student activists and members of the Dao Din Group who came out to show their solidarity with their fellow student activist, “Pai Dao Din”, during a hearing in front of the Khon Kaen Provincial Court. The case began in 2017 and both the Lower Court and the Appeals Court convicted them. This year, the defendants authorized their lawyers to appeal the case in the Supreme Court.

Amidst the highly partisan political context over the past decade, the judiciaries have made decisions on several cases which have tremendous political implications and have led to various political pivots. The phenomenon continues even now, when public perception toward the Court as a “political actor” has become much more prominent. It is evident that cases have been filed successively to stifle people who criticize the Court. It has happened before and will happen again and is another major concern that warrants our close attention.

The arrests against Organization of a Thai Federation continuing throughout the year

Further arrests and prosecutions in politically motivated cases that have been taking place throughout 2019 are related to the suppression of freedom of expression concerning the Organization of a Thai Federation. Its core members, “The Three Musketeers”, are living in exile in Laos and continuing to run radio broadcasts from abroad, led by Chucheep Chivasut, aka “Uncle Sanam Luang”, who is now suspected to have been forcibly disappeared. Never, the Thai authorities continue to arrest and prosecute members of the public in Thailand, who have come out to express themselves through symbolic actions such as assembling in public places wearing black. In particular, such assemblies were held in various department stores on 5 December 2018 (the former king’s birthday).

According to TLHR, from September 2018 to December 2019, at least 21 individuals were charged for their connection with the Organization of a Thai Federation, in at least 11 cases. At least two of the suspects remain in prison and have not been bailed out.

The authorities often accuse them of committing an offence against Section 116 of the Penal Code (“sedition”) and Section 209 (“being a member of secret society”). Almost all of the suspects in these cases were held in custody in military barracks by the NCPO invoking Section 44. Charges were only pressed against them following their release from military barracks.

Most of the suspects who face charges are older persons, from 50 to 70 years of age. They are hired labor, motorcycle taxi drivers, masseurs, dressmakers, or small vendors, as well as some retired government officials. Many of them said that they were just listeners to the radio broadcast run by “Uncle Sanam Luang” and did not personally know those who ran the radio program. They casually listened to the program as the it offers information about economic and livelihood issues or political analysis. When they heard about the possible actions to express themselves, some decided to participate in the public action peacefully, until they were arrested by officials.

Many suspects in these cases insisted that they had not committed the alleged offences, but they were eventually indicted. 2020 will see the commencement of hearings and witness examinations concerning cases against the Organization of a Thai Federation. We must keep monitoring the trials and verdicts in all these cases. (for more detail, please see An overview of the cases against the Organization of a Thai Federation)

Despite the absence of Section 44, the Former Head of the NCPO is getting “used to” exercising his powers unchecked

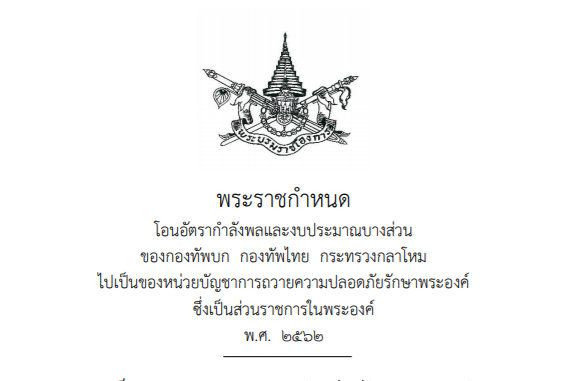

Under Gen Prayuth Chan-ocha’s role as “Prime Minister-elect”, the Parliament and members of the public should have the right to hold his exercise of administrative power to more account than when he was Head of the NCPO and seized power by staging a coup and ruled by personally appointing members of the NLA and members of the independent agencies. He even issued amnesty laws to provide immunity for his future exercise of powers, giving rise the persistent culture of impunity and a lack of accountability. A case in point is the promulgation of the Emergency Decree to Transfer Part of the Armed Forces to the King’s Direct Control and the vote to defeat a motion to set up a House Committee to Review the Impacts of Section 44.

On 30 September 2019, the cabinet invoked Section 172 of the 2017 Constitution to promulgate the Emergency Decree to Transfer Part of the Armed Forces’ Personnel and Funding to the King’s Direct Control. The armed forces would become part of the King’s Guards Forces in 2019 and some troops and funding from the 1st and 11th Infantry Divisions were to be under the King’s personal command. On 17 October, the Bill was approved by the House by 70 to 376 votes.

Nevertheless, this move has been questioned since the exercise of legislative power by the administration to promulgate an Emergency Decree can only be done when it concerns a matter of unmitigated urgency, pursuant to the constitutional exemptions. The government has failed to explain to the House why this action was urgently needed. It has only explained the rationale in the annex to the Bill, which states “the execution of duties to ensure safety, security and honor of His Majesty is pertinent and all preparations must be made comprehensively particularly, the allocation of troops commensurate to the execution of duties to ensure effective, prompt implementation and utmost safety”. It has failed to explain the Bill’s urgency as required by Section 172.

The Emergency Decree was pushed through using special powers. Even though the Parliament retains powers to investigate the promulgation, it can only examine if the promulgation has been done in compliance with the constitutional provisions concerning the reasons to legislate the law or not, and if the voting has been done lawfully or not. It is not authorized to review content of the Emergency Decree including the implication from the transfer of troops which could enable the King to exercise administrative power, a situation which would be in breach of the constitutional monarchy pursuant to Section 6 of the Constitution, which stipulates that the King shall be enthroned in a position of revered worship and shall not be violated. The exercise of power by the Prayuth cabinet to promulgate the Bill to transfer the troops unnecessarily could be viewed as an exercise of special power to avoid accountability, not dissimilar to the exercise of power by invoking Section 44 of the 2014 interim Constitution.

Meanwhile, opposition parties proposed an initiative to study the impacts of the exercise of powers through a motion to set up a House Special Committee to Explore the Impacts of the NCPO’s Announcements and Orders and the Exercise of Section 44’s Powers by the Head of the NCPO. The coalition parties lost the vote to implement the motion on 27 November 2019 but requested a revote. When the votes were cast again on 4 December 2019, the motion to set up the House Committee was approved. It again demonstrates how even though NCPO has become defunct, the Prayuth coalition continues to dominate in terms of legislative and administrative powers and can always avoid an attempt to hold it accountable, even in absence of Section 44.

The number of missing political refugees has increased to eight and hopes of their return home are fading

(Picture from Prachatai)

A number of Thai nationals have sought asylum abroad since the 2014 coup, seeking freedom and did not wanting to succumb to the power of the NCPO. Some were too scared of persecution by the military, of themselves and their families. The pro-democracy activists have found it yet again very daunting in 2019 when many political refugees have been persecuted, particularly those seeking asylum in neighboring countries.

Early this year, forensic tests confirmed that two of the three bodies found floating by the bank of the Mekong River in Nakhon Panom, in a brutally mutilated manner, belonged to Chatchan Bubphawan and Kraidet Luelert who were last seen at home in Laos together with Surachai Danwattananusorn. It was clear how the three dissidents ended up in such devastating situation and the news caused much concern among other political refugees from Thailand who remain living in neighboring countries. Several of them have applied for resettlement in a third country with international organizations. Many have changed their sleeping locations and avoid expressing their views online. Some remained hopeful that the situation would improve after the government-elect was formed.

But after the Royal Coronation, during which time the coalition was being formed, it was reported that “Uncle Sanam Luang”, or Chucheep Chivasut, Siam Theerawut and Kritsana Tupthai of the Organization of a Thai Federation were deported to Thailand by Vietnam. Both Thailand and Vietnam refuted the news. No one has seen them since. The news has terrified many other refugees since eight refugees in total have gone missing in the NCPO era. One day after the news broke that Uncle Sanam Luang and his friends were deported from Vietnam, Malaysia extradited Praphan, a suspect in the case against those who wore Organization of a Thai Federation T-Shirts, to face prosecution in Thailand, even though her refugee status was already recognized by the UNHCR in Malaysia.

Prior to the swearing in ceremony of the Prayuth Coalition government in the mid-July, at which time the NCPO was completely stripped of its power, Pavin Chachavalpongpun, one of the political refugees, and his male partner were injured in their home by an unknown culprit barging into their room in Kyoto, Japan. In the meantime, members of the Fai Yen band who were applying for third country asylum from Laos received death threats if they refused to turn themselves in.

Throughout the past five years, these activists criticized Thai politics and the monarchy through various means. And given the lack of serious attempts to investigate disappearance cases related to Thailand, many believe the NCPO is the mastermind of all these operations, even though all agencies under NCPO deny these claims.

After the ascensions of the Prayuth Coalition to ruling power, there have been no further clear-cut cases of harassment against Thai political refugees in other countries. The persons wanted by the NCPO, including four members of the Fai Yen band and Wat Wallayangkul, have already been rescued and granted asylum abroad. Nevertheless, Thai refugees are far from certain about their safety and security given that the government was not derived from free and fair elections.

Regrettably, toward the cessation of NCPO’s power, on 70 of the total 557 NCPO Orders and Head of the NCPO Orders were revoked. As NCPO Announcement No. 41/2557 has not been revoked, the NCPO still retains the power to summon individuals to report themselves. As a result, Thai refugees who sought asylum abroad as a result of being summoned by this Order to report themselves will not be able to return to their home anytime soon.