As the new Cabinet was sworn in before His Majesty the King on 16 July 2019, the junta-led National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) stepped down from power after having ruled the country for five years, one month, and 23 days. Nevertheless, the network of powerful political actors established under the NCPO regime has remained intact as they underwent a successful power inheritance. During its administration, the NCPO has designed the Constitution as well as several laws and political mechanisms to ensure it retains its tight grip on power and maintains the army’s pervasive political influence.

The NCPO has also left important long-lasting legacies – the institutionalization and systematization of human rights violations. In the long history of military coups d’ état in Thailand, the NCPO’s five-year rule was particularly characterized by widespread human rights abuses, especially by weaponizing the law. Since 2019, the newly elected government has taken office in Thailand. However, the pattern of human rights violations which was rampant under the NCPO regime continues with little sign of change.

For several years under the NCPO regime, various human rights violations occurred so frequently that they became normalized. With no end in sight, the abusive exercise of power by the NCPO has endured through time, although the junta-led council no longer existed on paper. On the occasion of the sixth anniversary of the 22 May 2014 coup d’ état, Thai Lawyers for Human Rights (TLHR) presents our report on Thailand’s human rights records one year after the NCPO regime ended. Our report highlights ongoing violations of the rights to freedom of expression and freedom of association. Our findings reveal that the “forms” of violations might have changed slightly over the regime change. However, the same old suppression of these rights has persisted and continues to be committed systematically.

1. At least 191 people are still harassed and visited at their homes by the authorities

Since the military coup in 2014, government officials have used the tactic of making intrusive “visits” of political activists, student activists, and opposition politicians at their personal spaces, including homes, educational institutions, and workplaces. Moreover, the authorities have consistently been contacting these target groups via various channels to monitor their activities. Such harassment constitutes one of the most dominant forms of human rights violations to have emerged during the NCPO regime and continues to occur at present.

Throughout the five years of the NCPO regime, TLHR has documented at least 592 reported cases of state-led harassment and intimidation. Among the reported forms of harassment were home visits conducted by state officials. Some people claimed that the authorities had pursued them at home over ten times during the NCPO rule. In the post-NCPO era, from 17 September 2019 to 30 April 2020, at least 191 people were visited at their homes or received threats from state officials. Some of them had engaged in political activism for a long time and were previously subject to harassment by the NCPO. However, many others were students who participated in political activities for the first time in the post-NCPO period. TLHR observed that local police officers are increasingly taking a dominant role in conducting the home visits, unlike during the NCPO’s rule when military officers led such operations. Military officers have not entirely backed away; they reportedly continue to visit the houses of some people on the “watchlist” to warn them to stay away from politics.

The intensity of surveillance and house visits regularly increases before important social events because activists often organize demonstrations during these periods. During the 2019 ASEAN Summit Meeting in Bangkok and the Royal Coronation in May and December of 2019, many people who had previously organized political activities were subject to home visits by the authorities. Furthermore, during the Assembly of the Poor’s large-scale demonstration in October, several protest leaders in more than ten areas also reported that the authorities visited them at home.

At the beginning of 2020, Thailand witnessed the rise of anti-government student protests. Multiple flash mob demonstrations and the “Run to Oust the Uncle” event were organized across the country. Consequently, during this time, provincial law enforcement authorities were closely monitoring student activists in many provinces. During the “Run to Oust the Uncle” event, at least 62 people were reportedly visited or followed by local authorities. As for the subsequent flash mob protests, at least 22 students were subjected to threats and intimidation by the authorities.

These harassments violate not only the fundamental rights and liberties of the victims, but also inflict negative impacts on their lives. For example, the officials visited one former MP candidate from the Future Forward Party in Lampang Province several times to ask him about the “Run to Oust the Uncle” activity. The visits unsettled the candidate’s 80-year-old father, who has diabetes, to the extent that he had to be hospitalized. Despite the father’s frail health conditions, police officers visited him at the hospital to ask questions about his son’s activities. In another case, the authorities harassed a Phayao University student who was preparing to organize a “Run to Oust the Uncle” activity by approaching his dormitory owner and trying to search the student’s room. The dormitory owner eventually asked the student to move out.

The authorities who had conducted this type of operation often claimed that they were following an “order of superior commanders” to “seek information”. Some officials were well-mannered and spoke to the targeted people with respect during their home visits. However, it must be noted that no law grants state officials the authority to intrude into private spaces and carry out active surveillance on citizens in this manner. The home visits trigger fear and anxiety among those visited. It also generates a chilling effect, discouraging people from expressing their political opinions. TLHR, therefore, regards these operations as a state-led campaign of intimidation and harassment, which violates the people’s rights to freedom of expression. Since the coup d’ état, this kind of harassment has been occurring so often that it has become normalized.

2. The prohibition of criticism against the monarchy: Invoking other laws and resorting to arbitrary detention and intimidation

The Thai government continues to suppress the expression of opinions related to the monarchy, especially by invoking the lèse-majesté law (Article 112 of the Criminal Code). After the 2014 coup, at least 169 people faced charges under this law. Out of this number, 106 allegedly defamed or insulted the monarchy, whereas the other 63 falsely claimed the name of royalty to seek personal benefit.

Since the outset of King Rama X’s reign, the number of cases filed and prosecuted under the lèse-majesté law has significantly declined. However, TLHR observes that the monarchy’s critics are still subject to intimidation and legal persecution under different laws, such as the Computer Crimes Act and the sedition law (Article 116 of the Criminal Code). TLHR observes that the judicial system increasingly dismisses charges of lèse-majesté and chooses to convict the defendants on other charges.

For example, political activist Karn Pongprapapan was arrested and detained on 7 October 2019 for posting about other nations’ royal histories on Facebook. He was later charged solely under Article 14 (3) of the Computer Crimes Act. “Niranam“, a 20-year-old Twitter user who has more than one hundred thousand followers, was also charged under the same law for tweeting a picture and message about King Rama X.

In terms of indictment and trials, both public prosecutors and judges tend to avoid pressing charges or prosecuting any person under the lèse-majesté law. For instance, Natee, a psychiatric patient, was sentenced to three years in prison under the Computer Crimes Act for posting a criticism of Rama IX online. Initially, he was charged under Article 112 of the Criminal Code, but later the public prosecutor switched to pursue the prosecution under Article 116 and the Computer Crimes Act’s Article 14(3) instead.

Many lèse-majesté cases that started during the five years under the NCPO are still ongoing. Notably, in most of these cases, the defendants decided to fight in Court to defend themselves. Some prominent cases include Siraphob who has been detained for almost five years without bail, Thanakorn who made a sarcastic online post about the King’s dog, Pannaree or Ja New’s mother who replied “Yeah” in response to a chat message that allegedly defamed the King, Anchan who posted 29 videos of Banpot who allegedly defamed the King, Waen Natthida who was a key witness in the lawsuit on the death of six people in Wat Pathumwanaram temple, Bandit Aneeya, a writer who faced the lèse-majesté charge on two counts, and many patients with psychosis who were accused of violating Article 112. Currently, all these cases have been transferred to civilian courts. TLHR continues to monitor them closely.

The monarchy’s critics do not only face persecution under the law but are also subject to arbitrary detention and intimidation and harassment by state officials. In November 2019, a Twitter user called @99CEREAL was arrested from their university to Klong Luang Police Station in Pathum Thani without any arrest warrant or summons. This person retweeted a post about the monarchy, so the police officers took them to the station for interrogation. The authorities questioned them about their political stance and demanded their personal information. The conversation was also video-recorded. The officers also asked for their mobile phone IP address, Twitter username and password, phone number, e-mail, and requested to see their chat messages. During the process, this Twitter user was not given the right to consult a lawyer. Eventually, they were pressured to sign a memorandum of understanding (MOU) requiring them to refrain from expressing any opinions about the monarchy on Twitter again. They were then released without charge.

TLHR also found that many social media users who expressed their opinions or shared information about the monarchy continue to be subjected to arbitrary detention and intimidation and harassment by state officials consistently. During October 2019 to April 2020, there were at least five reports of such cases. Despite the current COVID-19 crisis, the authorities continue to arrest and detain critics of the monarchy. Detainees have reportedly faced intimidation and interrogation about their personal life. Furthermore, the authorities also threatened to harm them if they told others about what happened. The actions of the state officials constitute illegal abuses of power. Nonetheless, most of these incidents have gone unreported.

The authorities also suppressed freedom of expression related to the monarchy by surveilling movie theatres, targeting those who refused to stand up to pay respect to the royal anthem before a movie began. In April 2019, some people were approached by the authorities who asked for their personal information and took photos of their ID cards.

Intimidation also happens in the form of a witch hunt. Some media channels exposed the personal information of the people who expressed their opinions about the monarchy and publicly condemned them. For example, one person who joined the “No Retreat, No More” flash mob protest in December 2019 took a photo of a protest sign with the background of the building painted with King Rama IX’s portrait. Many social media users verbally attacked this person. Later, she was forced to leave her job and got followed by the authorities.

3. The weaponization of the law and justice system as a political tool to suppress dissidents

The weaponization of the law and justice system aims at silencing dissidents and political opponents by using lawsuits to create a burden on the targeted individuals and helping the regime gain political advantage. This tactic has been widely used to violate human rights from the beginning of the NCPO regime to the present.

Regarded as political opponents of the NCPO, politicians from Pheu Thai Party, such as Wattana Muengsuk, Pichai Nariptapan, and Chaturon Chaisaeng, have fallen victim to judicial harassment since the army staged a coup in 2014. One prominent case was the lawsuit against eight Pheu Thai Party leaders who jointly spoke at a press conference on the fourth anniversary of the coup d’ état in 2016.

From 2019 to 2020, the newly elected government continues to use judicial harassment to target politicians from opposition parties. As the political landscape has shifted, the main target of harassment has become Future Forward Party. The party did not only face the Constitutional Court review that eventually led to its dissolution, but its nine executive leaders also face numerous criminal charges in ten cases due to the exercise of their freedom of expression. Former party leader Thanathorn Juangrungruengkit was charged under Article 116 for participating in the New Democracy student movement in 2015. Former secretary-general of the party Piyabutr Saengkanokkul was charged under the Contempt of the Court and the Computer Crimes Act for Facebook live-streaming a video that criticized the dissolution of the Thai Raksa Chart Party. Pannika Wanich, the party’s spokeswoman, faces charges under the Computer Crimes Act for her post in 2013 about Thailand’s government system. Five executive leaders of the party face multiple charges for organizing the “No Retreat, No More” flash mob protest at Pathumwan Skywalk. Lastly, Rangsiman Rome, an MP formerly affiliated with the party, faces charges of defamation filed by the Five Provinces Bordering Forest Preservation Foundation.

TLHR, however, has not incorporated statistical information into this report. While many other charges have been brought against the party’s executive leaders, inquiry officers have not summoned them to acknowledge some charges as yet. Further, several party coordinators across the country have been charged with organizing public demonstrations. These data have not been included in this report.

In October 2019, the Internal Security Operations Command (ISOC) accused 12 speakers of the seminar “Dynamics Towards Resolving the Southern Border Issues: Rewriting the Constitution” of violating the sedition law. The 12 accused included academics and leaders of seven opposition parties. During the seminar, the participants discussed the possibility of amending Article 1 of the Constitution. However, none of them have been summoned to acknowledge the charges before the inquiry officer yet. This type of retaliatory lawsuit is primarily wielded to silence political opposition and sabotage checks and balances essential in a functional democracy.

4. Article 116: The law on national security manipulated to secure the government’s security

Article 116 of the Criminal Code (sedition) contains an offense regarding the “security of the Kingdom” that has been interpreted broadly and used to target dissident citizens. During the NCPO’s five-year rule, at least 124 people, mostly protest leaders and vocal critics of the NCPO, have been charged with sedition.

Several people facing charges under Article 116 of the Criminal Code continue to fight a legal battle as their trials were transferred from military to civilian courts. Some examples of prominent sedition trials include the case of Chaturon Chaisang who spoke at a press conference that he was defying the NCPO’s summons order, the case of Sombat Boonngarmanong who posted online messages inviting people to protest against the coup, the case of Pansak Srithep who took part in the “Resistant Citizens” activity on denying the jurisdiction of military courts, and the case of Thanet Anantawong who posted a message criticizing the NCPO and the army. In the last case, the accused has remained in prison for almost four years, awaiting trial.

During the NCPO regime, some sedition cases stemming from political expression were filed to civilian courts. Most of these cases remain pending in court. Notably, the trials against “We Want to Vote” protest leaders, including the cases of MBK39, ARMY57, and UN62, have only reached the phase of witness examination even though the charges were filed in 2018.

Over the previous year, the court acquitted defendants in many sedition cases, pointing out that they did not violate the law in any way. For example, on 20 September 2019, the Criminal Court ruled that the leaders of a “We Want to Vote” protest on Ratchadamnern Road, dubbed as RDN50, were not guilty of sedition. Remarkably, the Court considered their actions a constitutional, lawful expression of political opinions and their criticism of the government a democratic exercise of free speech. Similarly, the trial against 15 defendants who circulated letters criticizing the draft 2017 constitution was transferred from the military Court to the civilian Court. Later on 25 March 2020, the Chiangmai Provincial Court dismissed all charges, including sedition, against the defendants on all counts. The ruling stated that the defendants’ letters were merely an expression of opinions in good faith. Both cases exemplify how the sedition law has been used to stifle freedom of expression and create an unnecessary burden for critics of the NCPO. Many of them had to spend several years fighting in the trial.

After the NCPO’s regime, at least three new cases have been filed under the sedition law. Two of them were against alleged affiliates of the “Organization for a Thai Federation,” while the other case concerned a former Red-Shirt leader who allegedly posted a video clip that invited people to protest against the NCPO.

The government crackdown on the “Organization for a Thai Federation” has led to many sedition cases that are still pending in Court. According to TLHR’s data, as of April 2020, at least 21 have been charged in 12 cases. Most cases were filed against citizens who wore a black t-shirt to visit public spaces on 5 December 2018. Almost all of them have been charged with sedition and membership in a secret society.

Interestingly, the Court has already handed a verdict in at least five cases related to the Organization for a Thai Federation. In four of these cases, the prosecutor filed for the charges of sedition and membership in a secret society. However, in January and March 2020, the Court ruled that all defendants were not guilty of sedition in three cases. This trend shows how law enforcement has tried to weaponize the law to suppress dissenting opinions, even though such an act of dissent merely means wearing a black t-shirt.

5. The increasing enforcement of the Computer Crimes Act to target “fake news”

The Computer Crimes Act B.E. 2550 (2007) was amended by the junta-appointed National Legislative Assembly (NLA) in 2017. Contrary to this law’s spirit, the authorities have been wielding it as a tool to suppress online content that is critical of the government.

Throughout the NCPO’s five-year regime, TLHR documented that at least 197 people were charged under the Computer Crimes Act for expressing their political opinions on an online platform. In the post-NCPO period, from July 2019 to April 2020, at least 42 people have been charged with the Computer Crimes Act for expressing their opinions or publishing certain information online, accounting for 34 cases in total. Out of the 42, 37 were accused of sharing misinformation or “fake news.” At least 28 of them allegedly shared misinformation related to the situation of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Under the leadership of the Ministry of Digital Economy and Society, the government has set up the “Anti-Fake News Center Thailand” to monitor the spread of misinformation since November 2019. This center’s primary responsibility is to monitor and correct the information in the news that they regard as “fake” as well as to press charges against those spreading the fake news under the Computer Crimes Act.

TLHR found that some people charged for spreading misinformation by this center have exercised their freedom of speech by sharing unverified information, which contains criticisms about the government’s response to COVID-19. For example, Danai, a graffiti artist, was sued for criticizing the ineffectiveness of the COVID-19 screening measure at Suvarnabhumi Airport.

TLHR also found that the accused, in many cases, did not deliberately spread fake news. They unintentionally shared unverified information posted by others and did not “intend to cause damage to the country’s security or trigger a public panic.” However, all of them pleaded ‘guilty’ because they were concerned about the high costs of litigation.

Article 14(1) of the amended Computer Crimes Act B.E. 2560 (2017) stipulates that the Act shall not be used to punish perpetration that falls under the scope of the defamation offense in the Criminal Code. However, the Act continues to be utilized in this manner; for instance, in the case against people who shared rumors about the deputy police commissioner’s alleged involvement in the attack against “Ja New.”

TLHR has also noted some interesting verdicts in recent Computer Crimes Act cases. For example, one person was charged under this Act for sharing a post about the NCPO’s ineffective drug control policies from the “I Must Have Received 100 Million Baht from Thaksin” Facebook page. The Court acquitted the defendant because the post only negatively affected the image of the NCPO, not national security, which is the crucial element of the crime set out in Article 14(2) of the Computer Crimes Act.

In many other Computer Crime Act cases, the public prosecutor has ordered a non-indictment. Most of these cases were directed against critics of the NCPO and the army. For instance, Pinkaew Laungaramsri and Pichit Tamoon who made fun of the military in Chiang Mai province in an online post. In another case, Ekkachai Hongkangwan posted about the army’s historic defeat in the Ban Rom Klao battle, claiming that the Thai military never won any battles since World War II. Pichai Naripatapan posted about the Palang Pracharat Party’s “sucking” strategy to recruit MPs from other parties to join their camp and the government’s ban of Time magazine’s Asia Edition with General Prayut Chan-Ocha on the cover. Chanwit Kasetsiri shared a picture of General Prayut’s wife’s bag on Facebook. Lastly, Thanathorn Juengrungruengkit and the other two executive leaders of the Future Forward Party criticized the NCPO’s MP sucking tactics via a Facebook live stream.

These cases demonstrate how the NCPO and the army are using the Computer Crimes Act as a weapon to target influential public figures who vocally criticize their abusive exercise of power. Even though most of these cases get stricken down before they reach the Court, they often cause a significant burden on the defendants who must fight the legal battles for years.

6. Restricting public activities under the Public Assembly Act

The restrictions on organizing public associations or activities remains a crucial mechanism for the government to maintain its political dominance. After the NCPO regime ended, the restrictions on political activities and public gatherings imposed earlier were slightly relaxed. However, all public assemblies must follow stringent legal requirements and are subject to the state’s abusive supervision. The new government continues to utilize laws to regulate public assemblies and deploy officials to intimidate protestors, block venues, and monitor protest activities.

After the coup d’ état in 2014, the government actively employed the legal provision that prohibited a political gathering of over five people under NCPO Announcement No.7/2557 (2014) and Head of NCPO Order No.3/2558 (2015) to target political activists. At least 428 people faced charges under this offense.

During the NCPO regime, the junta-appointed National Legislative Assembly passed the 2015 Public Assembly Act. This law has become the primary tool that the government uses to control public assembly. The most striking pattern of abuse is the combination of enforcing the Public Assembly Act alongside the NCPO Order mentioned earlier, which prohibits political gathering. At least 276 people have been charged in such a manner.

Although the ban on political gatherings has been lifted, the government continues to use the Public Assembly Act to stifle freedom of association. This law creates additional burdens for protestors because it lays out an offense for “failing to notify the public assembly to a relevant authority 24 hours before the protest”. Many political activists and protest organizers have been charged under this Act for violating this offense. Further, the definition of “public assembly” has also been interpreted broadly by state officials. Activities, such as putting chilies and salt in front of the Government House, signature hunting to call for Senators to refrain from exercising their PM votes, and running events, can fall into this law’s scope.

From 17 September 2019 to 30 April 2020, TLHR received reports that government officials intervened in at least 42 public assemblies. The intervention resulted in the cancellation of 14 assemblies. At least 28 protest organizers have been charged under the Public Assembly Act in 18 cases during this period. For instance, at least 11 people got charged under this law for organizing the “No Retreat, No More” flash mob protest held by Future Forward Party in various provinces on 14 December 2019. Another example is the case stemming from the “Run to Oust the Uncle” event. Following the event, at least 17 organizers were charged for failing to notify the authorities, although the format of this event resembles more of a sports event.

In many cases, the assembly organizers successfully notified the authorities within the legal timeframe. However, they still faced charges for other activities, such as unauthorized use of amplifiers and blocking the traffic. Even though these are petty charges, they create additional unnecessary burdens for protest organizers.

To discourage public dialogue that might be critical of the regime, the government intervenes in academic and cultural activities not only by using the Public Assembly Act but also by pressuring the organizers. Even though these events are technically not a public assembly, the authorities often monitor them closely, thereby indirectly discouraging the organizers from incorporating content related to politics. At times, the organizers would be forced to change the venue, guest speakers, the activities’ format, and subject them to surveillance and monitoring throughout their activities.

During the five years of the NCPO regime, TLHR has received 361 reports of state intervention into public activities. Due to these interventions, 168 activities had to be canceled, while the other 193 were able to proceed.

During the post-NCPO regime, from 17 September 2019 to 30 April 2020, there were at least 55 reports of state attempts to shut down or intervene in public activities. Fourteen of them had to be canceled due to the state’s influence. For example, before the ASEAN Civil Society Conference/ASEAN Peoples’ Forum (ACSC/APF) that Thailand hosted in September 2019, security agencies requested a list of participants and tried to intervene by determining who should or should not attend it. Moreover, authorities tried to prohibit participants from expressing anti-government sentiment against governments in neighboring countries. Therefore, the event organizer decided not to accept the state sponsorship and relocated the forum to a different venue. In the past year, public seminars and Camps for Resistant Youth organized by Future Forward Party were interrupted by state officials eight times, causing disruption to the events. The “Run to Oust the Uncle” activity in 2019 also faced tremendous pressure and intense surveillance from the authorities.

7. Courts, private companies, independent organizations, and public figures filing lawsuits to silence their critics

The use of law to suppress criticism has become common practice not only for the government but also for the army and independent organizations, private companies, courts, and even foundations. The offense of criminal defamation has widely been wielded to critics of these organizations.

One example is the case filed by the Election Commission of Thailand (ECT) against activists and internet users who criticized its lack of transparency during the 2019 election. Charged with libel under Article 328 of the Criminal Code, the defendants include three activists who delivered a speech criticizing the ECT in the #IFuckingExist event and seven people who initiated the online campaign to impeach the ECT through the website change.org. All these cases are pending with the inquiry officer.

The Five Provinces Bordering Forest Preservation Foundation also filed a lawsuit against Move Forward Party MP Rangsiman Rome. Earlier, during the Future Forward Party’s no-confidence debate outside the Parliament, Rangsiman criticized General Prawit Wongsuwan for using his status as Deputy Prime Minister and President of the Foundation to his benefit.

In the past few years, the judiciary has received several public criticisms for the rising number of cases filed under the Contempt of Court and Violation of Court Powers charges. During the NCPO’s five-year rule, at least 18 people have faced charges for criticizing the Court and the justice system. Both of these offenses still play an important role in silencing critics until now. In April 2019, the Supreme Court’s Division of Election-Related Cases filed a charge of Contempt of Court against Sarinee Achavanuntakul, a writer and freelance translator, and Yuttana Nuanjarat, the editor of Bangkok Business Newspaper, for writing and publishing an article that criticized a supreme court verdict. Their article was titled Perils of Excessive Rule by Law (revisited), Case of Media Shareholding by MP Candidates. However, the case was later dropped when the accused agreed to publish another explanatory article admitting that the previous article used inappropriate language.

The Constitutional Court also added a legal provision outlining an offense of “violating the powers of the Constitutional Court” into the 2018 Organic Act on Procedures of the Constitutional Court. This clause prompted heated debates on whether it could be used to silence critics of the Constitutional Court, an institution that has played an active role in shaping Thai politics over the past few years. In August 2019, the Office of the Constitutional Court “invited” Assistant Professor Dr. Kowit Wongsurawat, Professor at Kasetsart University, and Yuttalert Sippapak, a film director, to meet with the Secretary-General of the Constitutional Court because both criticized the Court’s verdict. This was the first time that the Court summoned ordinary people for a meeting after the enforcement of this new offense. However, it remains unclear which powers the Court was exercising to summons them. Eventually, they faced no charges. After the meeting, both of them issued an apology for criticizing the Court.

Moreover, private companies also take part in this trend. Thammakaset Company, which is a chicken-farming business, filed several lawsuits against academics, human rights defenders, journalists, and numerous workers for publishing information alleging that the company had violated the rights of its workers. In another case, a mining company that received a concession to build a coal mine in Om Koi district of Chiang Mai filed a lawsuit against villagers, student activists, and academics who organized anti-coal mine activities. At least seven people faced charges in this manner between October and November 2019.

Apart from the lawsuits initiated by private organizations and companies, influential people or public figures use lawsuits this way too. For instance, while Thamanat Promprow was running as an MP candidate, he asked his representative to file a defamation charge against Phayao University students who questioned the practice of vote-buying by Palang Pracharat Party. Once he took office and became Deputy Minister of the Agriculture and Cooperatives Ministry of Thailand, he filed a lawsuit against people who criticized him for his past criminal record in drug-related offenses. Reportedly, he has also filed many other defamation charges.

This manner of weaponizing the law can be considered a strategic lawsuit against public participation or SLAPP. It affects the rights and liberties of the people to criticize, present alternative information, and investigate the government’s exercise of power. Should this kind of human rights violation continue, it would discourage people from speaking out in the public interest.

8. Court cases have been transferred from military courts and civilian courts, but military camps are still used for imprisoning civilians

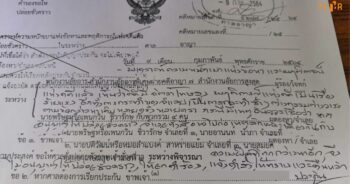

During the NCPO regime, the trial of civilians before military courts was arguably the most prominent political suppression tactic, mainly targeting vocal dissidents who opposed the coup. According to the Judge Advocate-General’s Office, 2,408 civilians were tried before military courts in 1,886 cases during the NCPO’s five-year rule. On 9 July 2019, General Prayut Chan-Ocha invoked his power under Article 44 of the Interim Constitution to issue Head of NCPO Order 9/2562 (2019), revoking 78 unnecessary NCPO orders. The Head of NCPO Order also stipulates that political cases tried in military courts must be transferred to civilian courts. No changes shall be made to the procedure already undertaken under the jurisdiction of military courts. All political cases were then transferred from provincial military courts to provincial civilian courts.

According to the statistical record of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), 162 cases were transferred to civilian courts. Among these cases, 21 are under the responsibility of TLHR. Some of these cases have been ongoing since the 2014 coup. Some cases took longer than six years, and the Court still has not issued a verdict. This undue delay in the process has created a significant burden on the defendants.

TLHR observes that the cases transferred from the military courts, especially political cases, are under the “military-led justice system.” The accused or defendant was initially interrogated inside a military facility without any oversight or human rights protection mechanism. The interrogation notes taken during this process was then used as evidence in Court. The accuser who was usually a military officer affiliated with the NCPO often used these pieces of evidence to request an arrest warrant from a military court. Later, military officers acted as inquiry officers, and military prosecutors determined whether to indict the accused. One must question if a normal justice procedure – both civilian public prosecutor and civilian courts – should take over these illegitimately conducted cases.

Apart from the trial of civilians before military courts, the NCPO also has set up a temporary prison (11th Infantry Regiment Prison) since September 2015. The junta claimed that this prison was a secure and appropriate place for jailing national security inmates. Many civilians have been imprisoned there, including the suspects in the case of the bombing at Ratchaprasong Intersection, the lese majeste suspects including “Moh Yong” who got a blood infection and later died in a temporary military prison, amongst other cases.

In March 2019, the 11th Infantry Regiment Prison was relocated to Thung Song Hong sub-district in Lak Si district. The Ministry of Justice announced that the prison was also relocated to the new location and changed its name to the Temporary Prison of Thung Song Hong sub-district. The authorities continue to detain ‘national security’ suspects here.

The current government continues to put civilians in military prisons. According to the Department of Corrections, as of 7 February 2020, the Temporary Prison of Thung Song Hong sub-district is jailing six prisoners. Three of them are suspects involved in a bombing incident in the south. Two are allegedly involved in the bombing incident at Ratchaprasong Intersection, and the other is a lese majeste prisoner. The total number of civilians in military prisons (including both the prison in Nakhon Chaisri and Thung Song Hong) stands at 53.

TLHR found that the imprisonment of civilians in a military prison results in difficulties for lawyers to reach their clients. First, the lawyers will be subject to a complicated visitation procedure designed differently from that of a normal, civilian prison. Second, military guards will closely monitor the visitation and limit the visitation time, even for a meeting between the attorney and client. Lawyers who plan to prepare their clients before trial must submit a list of questions or memo for the military officers to screen them first. This procedure limits the right to a fair trial and the right to defend oneself in Court with full capacity. Moreover, many prisoners have also reported that they were tortured and faced solitary confinement in these military prisons.

9. NCPO Orders, NLA Laws, and Court Verdicts Endorsing the Coup Regime

Before General Prayut terminated his role as the Head of the NCPO, he revoked 78 out of 564 orders and announcements issued by the NCPO (which totaled 214 orders, 133 announcements, and 217 Head of NCPO Orders). Many orders and announcements issued by the coup cabinet are, nonetheless, still in effect.

Persisting orders and announcements continue to restrict people’s rights and liberties. For example, NCPO Order No.41/2557 (2014) sets the punishment for not reporting to the NCPO after being summoned. People charged under this law, therefore, still face a criminal offense in Court. At least 14 people have been charged under this law, including Professor Dr. Worajet Pakirat, an academic from Thammasat University, and political activists who chose to flee to other countries because they refused to report to the NCPO. As this order remains in effect, if they return to Thailand, they will face prosecution.

The NCPO Orders, which increase military powers over civilian officers, are also still enforced under the new government. For example, Head of NCPO Order No.23/2558 (2015) authorizes military officers to arrest and detain a drug offender for preliminary interrogation for up to three days. This order allows military officers to resort to extrajudicial means, such as torturing suspects. In April 2020, military officers detained two villagers in Tat Panom district of Nakhon Panom province and tortured them to force them to confess that they sold drugs. One of the torture victims died, and the other was severely injured.

Head of NCPO Order No.3/2558 (2015) and No.13/2559 (2016) grant military officers sweeping and unchecked powers to interrogate, arrest, and detain a person in an unofficial detention facility for up to seven days. The Court has no authority to oversee this exercise of power under these orders.

Head of NCPO Order 51/2560 (2017) grants military officers more power by expanding the scope of power and roles of the Internal Security Operations Command (ISOC) into various areas. Under this order, military powers trump civilian powers. The ISOC remains influential in the post-NCPO era.

Several NCPO orders also violate community and environmental rights, such as Head of NCPO Order No.17/2558 (2015), No.3/2559 (2016), and No.74/2559 (2016) which allows forced evictions in areas intended to establish the Special Economic Zones (SEZ). Under this order, there is no need for regulatory measures or assessments of the impacts on the environment, and human rights of nearby communities.

The legality/constitutionality of NCPO orders and announcements cannot be challenged under standard mechanisms because Article 279 of the 2017 Constitution endorses the legitimacy of these orders and announcements.

Apart from these orders, the NCPO-appointed National Legislative Assembly also passed 444 acts, all of which are still effective. Almost all of them were passed in a rush and lacked participation. Their content violates the rights and liberties of the people. There is little possibility of amendment given the current condition of the Parliament.

Meanwhile, the judiciary serves to strengthen the NCPO regime by using a court verdict to endorse the coup d’ état and the exercise of power by the coup makers. It also grants legal immunity for the NCPO, protecting them from any form of accountability. These verdicts are still in effect. Even though political cases have already been transferred to civilian courts, these courts are still reproducing a similar idea endorsing the coup. For example, in the case of Ponlawat, who circulated anti-dictatorship pamphlets, the Rayong Provincial Court ruled on 26 March 2020 that the defendant was guilty, endorsing the legitimacy of the coup and the NCPO’s restriction of rights and liberties during that time even though the NCPO no longer existed.

Some civilian courts still use revoked orders and announcements to prosecute people, especially the offense of political gathering of over five people under Head of NCPO Order No. 3/2558 (2015), which has been revoked since 11 December 2018. The Supreme Court still ruled in the case of Apichat Wongsawat that the defendant is guilty. The Court interpreted that the Head of NCPO Order No.22/2561 (2018), which revoked Head of NCPO Order No. 3/2558 (2015), does not retrospectively impact the cases that started earlier than the issuance date of the Head of NCPO Order No.22/2561 (2018). This verdict has sparked criticism because the Court’s analysis allows the invocation of revoked laws for prosecuting people, thereby violating Article 2 (2) of the Criminal Code.

The endorsement of the coup can still be seen in the lawsuits against political activists who organized political activities. The public prosecutor still charged them under Head of NCPO Order No.3/2558 (2015). Many defendants are still fighting in Court under this offense even though the law has been revoked. For example, the case of “We Want to Vote”, dubbed as UN62 and the case of anti-referendum movement in Bang Sao Tong.

10. At least 28 political prisoners, at least 104 political activists living in self-imposed exile abroad

The NCPO has left two important legacies. The first is the large number of people who remain imprisoned as political prisoners. The second is those who had to flee their homes and become ‘political refugees’. They still cannot return to Thailand despite the inauguration of a new government.

According to TLHR’s data, as of April 2020, at least 28 political prisoners remain imprisoned due to their political activities since the 2014 coup. Almost all of them were sentenced by military courts during the NCPO regime and, therefore, received unfair, long sentences. 17 of those imprisoned were convicted for violating Article 112 of the Criminal Code (lese majeste). Three of the prisoners were convicted of sedition for their alleged involvement in the Organization of a Thai Federation. The other eight faced convictions for charges related to possession of weapons.

During the six-year period in which NCPO Orders were in effect, several people decided to flee the country because they did not want to report to the authorities under a summons order. Many also fear being monitored by military officers and being arrested under Article 112 of the Criminal Code (lese majeste) as well as other offenses related to possession of weapons. They believed that they could never win a lawsuit against the powerful junta. According to TLHR’s data, 104 people have been forced to live in self-imposed exile after fleeing the persecution of the NCPO and its orders.

Political refugees and asylum seekers face constant harassment and live precarious lives. In July 2019, when the NCPO was stepping down from power, Assistant Professor Pavin Chachavalpongpun, an academic and political refugee, was attacked at his house in Japan. Around the same time, the Fai Yen group, which was seeking asylum outside Laos, received death threats. The threats reportedly ordered them to surrender to the Thai authorities; otherwise, they would be murdered. They had to live in extreme fear and anxiety until they successfully relocated to a third country.

Among the political activists living in self-imposed exile in neighboring countries, there are at least six reported cases of potential enforced disappearance, three of which are related to the Organization of a Thai Federation, including Mr. Chucheep Cheewasut (Uncle Sanamluang), Siam Teerawut, and Kritsana Tapthai. In November 2019, Vietnam reportedly handed these political activists back to Thai authorities; however, both the Vietnamese and Thai governments denied the report. No one has been able to contact them since then. Moreover, there was another report of two cruel deaths of political asylum seekers. When found, their bodies appeared to have been brutally beaten. To date, there is no clear information on what happened to them and who killed them.

The culture of impunity is rampant, not only for violations against asylum seekers but also for assaults against activists that continued throughout the first months of 2019 when the NCPO was still in power. At least seven attacks against three activists were reported, including the brutal attack on Sirawit Seriwat or “Ja New” who got severely injured on a public footpath. On 20 February 2020, police officers announced that they would withhold the investigation into this attack because they lack evidence that could determine who the perpetrators are.

11. The power structure established by the NCPO will remain in Thai society

Almost one year has passed since the NCPO’s regime ended. Nevertheless, human rights violations through the exercise of state powers persists in Thai society. The most impactful inheritance of the NCPO’s regime is the 2017 Constitution. The NCPO has planned out its power succession since the beginning by organizing an unfree and unfair constitutional referendum and setting up constitutional provisions that facilitate it to remain in power. The NCPO set out the provision that the junta shall handpick Senators. It also established the Committee on the 20-Year National Action Plan to ensure that subsequent governments follow its governance strategies for at least the next 20 years. Furthermore, the NCPO, together with the junta-dominated NLA and the Senators, appointed members of independent organizations that were supposed to perform checks and balances on the government. Lastly, the army has significantly expanded its role and institutionalized its power to intervene in politics. The NCPO’s legacies are creating more problems that have become chronic in Thai society.

TLHR has created four key recommendations for addressing the legacies of the NCPO’s coup. The recommendations are as follows:

- Limit the power of the army and reform the security sector

- Reform the justice system and guarantee access to justice

- Provide remedies for the damages inflicted on people affected by the 2014 coup d’état

- Revoke all NCPO orders and announcements, laws passed by the NLA, and verdicts endorsing the NCPO’s legitimacy.

Read more in our report, “5 Years of NCPO: Enough is Enough. Recommendations on how to tackle the coup legacies“, the full version of which is available here and here.

TLHR believes that these issues must be pushed further to end the legal and political structure that supports the culture of impunity for those who staged the coup. We must create a new system that prevents abuses of state power, restores democracy, and establishes the rule of law in Thailand.